Dive On In!

The Often Overlooked Strategy to a Smoother ACL Recovery

We've all had that patient.

The 6-week post-op ACL’er who's chomping at the bit, but their knee blows up if they so much as look at a leg press.

Their quad activation is poor, their gait is hesitant, their cardio is disappearing, and you can see their motivation heading south for the winter.

You're stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Push too hard and you flare them up, risking effusion and pain that sets you back days.

Go too slow, and you risk atrophy, deconditioning, and a disengaged athlete.

It’s one of the most common clinical dilemmas we face.

But what if the most effective tool to bridge this gap isn't in your weights area at all, but outside in the pool?

After digging into a fantastic clinical commentary by Buckthorpe and colleagues (2019), I've been reminded that aquatic therapy isn't just a "nice to have"; it's a powerful, evidence-based adjunct that can solve many of our biggest early-stage rehab headaches.

Especially when the wounds have closed up.

Let's break down the clinical applications.

Six Evidence-Based Applications in ACLR Rehab

The paper outlines six key areas where the unique properties of water can be clinically used to enhance our outcomes.

Pain and Swelling Management: The hydrostatic pressure of water is a clinician's best friend for an effused knee. The paper notes that immersion to 120cm subjects the limb to nearly 90 mmHg of pressure—higher than diastolic blood pressure—which facilitates fluid shifts and supports lymphatic drainage. This, combined with the desensitising effect of water on sensory nerve endings, can significantly reduce pain perception and allow for more productive ROM and activation work.

Early Gait Re-education: We know how crucial it is to restore normal gait patterns early. The buoyancy of water offers a progressive-loading environment that's impossible to replicate on land. You can offload 40-60% of a patient's body weight by varying immersion depth from the waist to the chest. This allows for the practice of optimal walking mechanics far earlier than a patient could tolerate full weight-bearing, helping to mitigate the development of compensatory strategies.

Cardiovascular Conditioning: The detraining effect post-ACLR is significant. Deep-water running and other aquatic exercises provide a robust cardiovascular stimulus without the joint impact. Evidence shows this type of training can maintain VO2 max and running performance in athletes during non-weight-bearing periods. Clinically, it's vital to remember that the typical HR response is blunted by 10-15 bpm in water versus land for an equivalent intensity, due to increased stroke volume. We must adjust our monitoring parameters accordingly.

Accelerated Motor Pattern Retraining: How often do we delay functional movements like squats or lunges due to load intolerance? The pool allows us to introduce these patterns far earlier. This facilitates the simultaneous training of motor control in the water while we focus on isolated strength in the gym, creating a more holistic and efficient rehab process. Studies show that jumping and balance tasks in water yield similar functional improvements to land-based training, with the obvious benefit of being safer to implement sooner.

Early Introduction of Plyometrics: Restoring the Rate of Force Development (RFD) is critical, yet true plyometrics are a late-stage modality due to high impact forces (2-6x body mass on land). Aquatic plyometrics are a game-changer here. The paper highlights a 45-60% reduction in peak ground reaction forces in water. This allows us to safely introduce the stretch-shortening cycle mechanics and neuromuscular stimulus for power development long before the joint is ready for land-based impacts, and with reports of less subsequent DOMS and inflammation.

Load Management and Recovery: In the later stages, as on-field work begins, the pool becomes a perfect tool for managing cumulative load. A recovery session involving deep-water running can accelerate recovery. One cited study found that a deep-water running group recovered leg strength significantly better (only a 7% loss) compared to other groups (20% loss) 48 hours after a strenuous plyometric bout, with 40% less perceived soreness.

A Phased Clinical Framework for Implementation

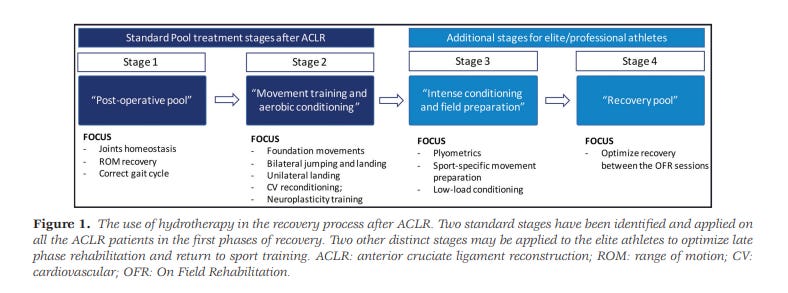

The authors provide a superb, criterion-based 4-stage protocol that aligns aquatic therapy with a modern functional recovery process.

Stage 1: 'Post-op pool' (approx. weeks 2-4): Focus is on joint homeostasis, ROM recovery, and gait correction once wounds are fully healed.

Stage 2: 'Movement training and aerobic conditioning' (approx. weeks 5-12): This is where we introduce foundation movements (squats, lunges) and use deep-water running for CV fitness and motor patterning.

Stage 3: 'Intense conditioning and field preparation' (approx. weeks 13-18): For athletes, this stage is an adjunct to land-based work, allowing for higher-intensity plyometrics (e.g., unilateral tasks) and sport-specific drills in a load-managed environment.

Stage 4: 'Recovery pool' (approx. weeks 19+): Once the athlete is in on-field rehab, the pool is primarily used to optimise recovery between high-load sessions and manage training density.

Key Clinical Takeaways & Precautions

The primary safety concern is infection risk. Do not commence aquatic therapy until surgical wounds are fully healed, free of any signs of phlogosis (redness, swelling, heat), and all stitches have been removed. This requires explicit medical clearance.

Aquatic therapy is a complement to - not a substitute for - a progressive, land-based strength and conditioning program. Its primary value is highest when the knee is load-intolerant.

Don't just prescribe exercises. The goal is motor learning, so provide specific feedback on technique to ensure you are retraining optimal patterns, not reinforcing poor ones.

Remember the blunted heart rate response (10-15 bpm lower) when prescribing and monitoring cardiovascular work to ensure you're hitting the desired physiological stimulus.

By integrating a structured aquatic therapy program, especially in those challenging early phases, we can better manage pain and effusion, accelerate motor learning, maintain patient fitness and motivation, and ultimately, build a more robust foundation for a successful return to sport.

In Summary

Next time you have that ACLR patient stuck in the frustrating cycle of 'load, swell, rest, repeat', remember that the pool offers a powerful clinical solution. It’s not about taking it easy; it’s about training smarter.

By leaning into the principles of hydrostatics and buoyancy, we can keep our athletes conditioned, facilitate motor patterning, and manage their load more effectively than we ever could on land alone. It’s a chance to provide our patients with both a psychological and physiological boost when they need it most.

By integrating a structured, evidence-based aquatic program like the one outlined by Buckthorpe and his team, we're not just adding another exercise; we're adding a vital tool to our clinical arsenal that can help us build more resilient, confident athletes from day one.

Yours in (knee) health,

Mick Hughes

Founder of The ACL Hub

Reference

[1] Buckthorpe, M., Pirotti, E., & Della Villa, F. (2019). Benefits and Use of Aquatic Therapy During Rehabilitation After ACL Reconstruction - A Clinical Commentary. The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 14(6), 978–993.