If there's one question that sparks more debate than "who's the GOAT; LeBron or MJ?" - in the sports medicine world, it's got to be: "Which graft is best for an ACL reconstruction?"

Patella Tendon or Hamstrings?

It's a massive decision for both the surgeon and the patient/athlete, and let's be honest, it can feel like a bit of a minefield.

Well, grab a cuppa, because a really interesting study has shed some more light on how this choice might play out in your rehab journey, particularly how quickly you hit those crucial milestones.

We're diving into a secondary analysis from the ACL-SPORTS Trial by Smith et al. (2020), which took a closer look at athletes undergoing ACL reconstruction (ACLR) and how their graft choice – specifically Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone (BPTB) autografts, Hamstring Tendon (HT) autografts, or soft tissue allografts (ALLO) – affected their rehab timelines and ability to meet return-to-sport criteria.

(Read the full text paper here)

What Did the Study Look At?

The researchers wanted to see if the type of graft used in ACLR influenced how long it took for athletes to meet specific post-operative clinical milestones and, ultimately, return-to-sport (RTS) criteria.

They also compared clinical outcomes like strength and patient-reported function at different stages.

They followed 79 athletes (aged 13-55, all Level I or II sportspeople) who had undergone ACLR with either a BPTB autograft (taking a piece of their own patellar tendon), a HT autograft (using their own hamstring tendons), or an allograft (using donor tissue).

Now, when we talk about "Level I or II" athletes, what does that actually mean in terms of the demands on their knees?

Based on classifications that consider knee joint load:

Level I sports are those that involve a lot of jumping, cutting, and pivoting. Think of your classic team sports like soccer, volleyball, and handball. These activities place really high demands on the ACL.

Level II sports involve more lateral movements but generally less pivoting than Level I. This category includes technical sports like track and field, alpine skiing, and snowboarding, as well as martial arts such as judo, karate, and boxing, aesthetic sports like dance and gymnastics, and even risk sports such as rafting and rock climbing. Still pretty demanding stuff!

For context, Level III sports (which weren't the primary focus of this study's participants) typically involve straight-ahead activities with no jumping or pivoting, like running, cycling, swimming, weight lifting, and bodybuilding.

So, the athletes in this study were involved in sports that put a significant amount of stress through their knees, which is important when we're thinking about their recovery and return to those activities.

It's worth noting that the early post-op rehab wasn't standardised across everyone before they enrolled in the specific RTS program part of the study, which actually makes the findings a bit more like what we see in the real world.

To get into the formal RTS program (the ACL-SPORTS clinical trial), participants first had to hit certain targets between 3 and 9 months post-surgery:

Full knee range of motion

Minimal to no knee swelling

Quadriceps strength of at least 80% of the uninjured side (Quadriceps Index or QI ≥ 80%)

Successfully complete a walk/jog progression

Once enrolled, they all did 10 sessions of a comprehensive RTS program over 5-7 weeks, focusing on progressive strengthening, neuromuscular training, plyometrics, and agility.

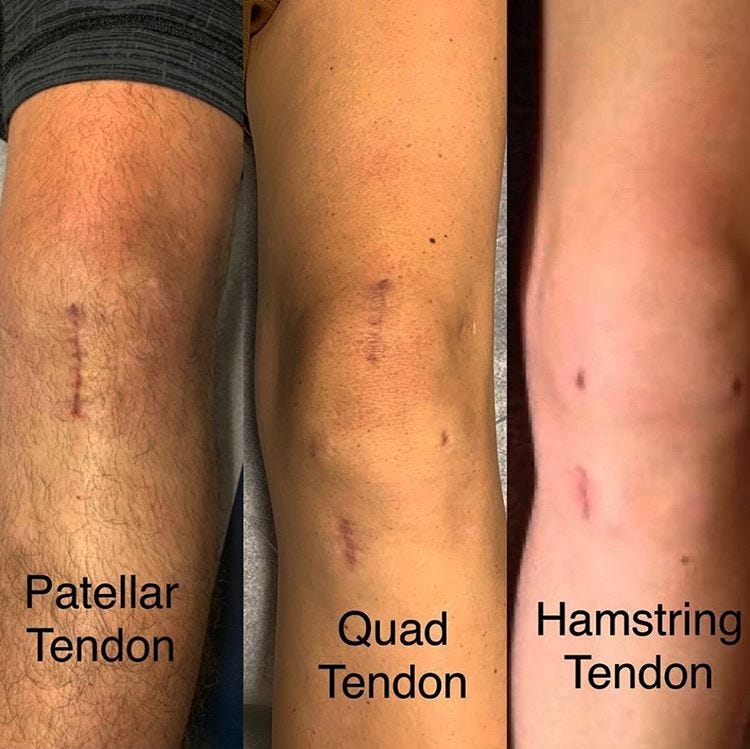

Image from Central Performance Physio Website (https://centralperformance.com.au/)

So, What Did They Find?

This is where it gets really interesting for us as clinicians and for you as patients navigating your recovery.

Timelines Mattered.

BPTB autograft group took significantly longer to meet both the enrollment criteria for the RTS program and the final RTS criteria.

The BPTB group took about 6 weeks longer than the HT group and a chunky 9.5 weeks longer than the allograft group to be ready to start the specific RTS program (which, as a reminder, required full knee range of motion, minimal swelling, a Quadriceps Index of ≥80%, and completing a walk/jog progression).

When it came to actually being cleared for return to sport, the bar was set pretty high. Athletes had to meet several criteria, achieving at least 90% on each of the following compared to their uninjured side or pre-injury status:

Quadriceps Index (QI): A measure of their operated leg's quad strength.

Limb Symmetry Index (LSI) on all 4 hop tests: This involved a battery of hop tests to assess power and control, including the:

Single hop for distance

Crossover hop for distance

Triple hop for distance

6-meter timed hop

Knee Outcome Survey-Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADLS): A patient-reported score on how their knee felt and functioned during daily activities.

Global Rating Scale (GRS): Where the patient rated their knee's function on a scale of 0 to 100, with 100 being pre-injury function.

The BPTB group was 12 weeks (that's about 3 months!) slower than the HT group and 15.5 weeks slower than the allograft group to meet all these demanding RTS criteria.

On average, the BPTB group met RTS criteria at over 10 months post-op, while the allograft and HT groups were around 6.5 and 7.5 months, respectively (Smith et al., 2020).

After completing the RTS program, the BPTB group had a lower average Quadriceps Index (QI) (86%) compared to the HT group (96%) and the allograft group (97%).

This suggests that regaining quad strength might be a bit more of a battle for those with a BPTB graft even after a dedicated training block, and this was before they'd even hit that 90% QI mark required for the final RTS clearance.

But in the long run did it matter?

Interestingly, by the one-year mark post-ACLR, there were no significant differences in any of the clinical outcome measures (including strength, hop tests, and patient-reported scores) between the three graft groups. It seems the BPTB group eventually "caught up."

What Does This Mean for You?

Okay, this is the juicy bit; how can we use this info?

For Patients:

Managing Expectations (Especially with BPTB): If you and your surgeon have opted for a BPTB graft, this study suggests your road to hitting those key rehab milestones might be a bit longer. This isn't necessarily a bad thing (more on that later!), but it's crucial for your mindset. Don't get disheartened if you see others (with different grafts) progressing a tad quicker. Your journey is your own.

If you have a BPTB graft, that quad muscle on your operated leg needs extra love and attention. Really focus on your strength work, especially heavy resistance training. This might need to be a continued focus even as you move into later-stage rehab.

This study adds another piece to the graft choice puzzle. Have an open chat with your surgeon about the pros and cons of each option, considering your sport, goals, and how these potential timeline differences might fit with your life.

For Health Professionals:

Use this information to help set realistic expectations. For BPTB patients, highlight the potential for a longer timeline to meet specific criteria and emphasise the importance of consistent quad strengthening.

We may need to be even more diligent with unilateral quadriceps strengthening throughout the RTS phase for our BPTB patients. Ensure the loading is appropriate (i.e., sufficiently heavy) to drive those strength gains.

Smith et al. (2020) raise a really thought-provoking point. While a faster return to sport (seen with HT and allografts in this study) might seem like a win, we know from other research that returning earlier (especially before 9 months) can increase the risk of a second ACL injury (Grindem et al., 2016). The authors suggest that the inherently longer recovery and RTS timeline for the BPTB group might inadvertently offer a protective effect by simply allowing more healing time and more time for the graft to mature before facing the demands of sport. This is a massive consideration. Perhaps "slower" isn't always a drawback in the grand scheme of long-term knee health.

The study noted the allograft group was older, which often aligns with surgical trends. However, this allograft group was still highly active. While the study adjusted for age and sex, these factors always play a role in our clinical reasoning.

A Few Caveats

As with any study, there are a few things to keep in mind.

The early rehab before entering the formal RTS program wasn't controlled, and many different surgeons were involved – though this does make it more "real-world.

Also, all participants were athletes aiming to return to fairly high-level sport, so the findings might not apply to everyone.

The Take-Home Message

This research by Smith et al. (2020) provides valuable insight into how graft choice can influence early to mid-stage recovery timelines after ACLR.

Athletes with BPTB autografts, on average, took longer to hit key rehab milestones and meet RTS criteria, and they showed slower quadriceps strength recovery immediately after an RTS program.

However, it's not all about speed.

The fact that these athletes returned later might actually be a good thing for reducing re-injury risk. By the one-year mark, everyone seemed to reach a similar functional level.

The key is individualised rehab, managing expectations, and a relentless focus on those crucial strength gains, especially for our BPTB folks!

Keep up the great work in your rehab, and remember, it's a marathon, not a sprint.

Until next time,

Mick Hughes (Sports Physiotherapist)

Founder, The ACL Hub

References

Smith, A. H., Capin, J. J., Zarzycki, R., & Snyder-Mackler, L. (2020). Athletes With Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Autograft for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Were Slower to Meet Rehabilitation Milestones and Return-to-Sport Criteria Than Athletes With Hamstring Tendon Autograft or Soft Tissue Allograft: Secondary Analysis From the ACL-SPORTS Trial. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 50(5), 259-266. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.9111

Grindem, H., Snyder-Mackler, L., Moksnes, H., Engebretsen, L., & Risberg, M. A. (2016). Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(13), 804-808.